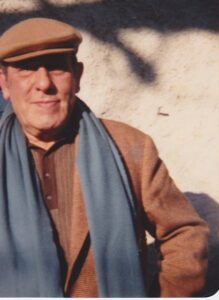

René Char

I’ve worked on the poetry of Char for over forty years and have long admired the life he lived, his faith in human endeavour, his fears for our planet’s future, and his unique writing style. When I visited him at his home in Provence in 1982, six years before he died, I found a gracious host who expressed delight and surprise that his poetry was taught and appreciated in as distant a place as the Antipodes! While we toured his garden, redolent with lavender bushes and aromatic herbs, he pointed in the direction of places and things that had inspired him over long years: the lofty, snow-capped Mont Ventoux; the rugged mountain chain of Les Alpilles; the river Sorgue that runs through the village; the Fontaine de Vaucluse, where it gushes from its underground course in the hillside; the clayey soil on which we stood; the plant and bird life around him, thriving in the Provençal sun. Clearly, the poetic wisdoms and philosophical meditations that straddle his poetry sprang in part from his affinity with nature and his deep respect for the laws and wonders of landscapes that were close to hand.

Char was born in 1907 in L’Isle-sur-Sorgue, a village in rural Vaucluse in the heart of the Provençal countryside. In the early 1920s he embarked on a poetic career that spanned seven decades. In 1930 he joined the surrealist movement in Paris but took leave of the group and its aesthetic tenets in 1935. Henceforth, he forged friendships with leading modern artists of the century – notably Georges Braque, Joan Miró, Vieira da Silva, Nicolas de Staël, and Alexandre Galpérine – many of whom illustrated his poems. In turn, he celebrated their achievements in poetic homages of highly metaphoric, interpretive charge. Between 1941 and 1944, at the height of the Second World War, he served in the French Resistance in the South of France, fighting in dangerous situations alongside heroic comrades. It was an experience that led to the publication in 1946 of Feuillets’d’Hypnos, a war journal of poetic notations that brought him to wide public attention and consolidated his growing fame. His first collection of aphorisms, the 1936 Moulin premier, established his predilection for a genre he mastered and adopted in numerous collections, the last, Eloge d’une Soupçonnée, published in 1988, just months before he died. Often described as hermetic, his work befits one concerned with the complexity of the human condition and the mysteries of art, life, nature, the cosmos, and the power of words.

‘How did I become a writer? Like a bird’s feather against my windowpane in winter. All at once a battle of embers arose in my hearth, never to die down.’ (Char, La Bibliothèque est en feu)

‘Only my fellow, man or woman, can rouse me from my apathy, release my poetry, fling me against the limits of the ancient desert that I may conquer it. Neither heaven, nor the earth, our destiny, nor all that has us quail.’ (Char, La Bibliothèque est en feu)